“You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know.”― René Daumal

As I write this, I feel exhilarated and inspired. You see, I got to stand at the top of Wyoming’s tallest mountain, Gannett Peak, last Thursday.

I hike about 1,000 miles a year, and I’ve climbed several peaks, including Wind River Peak, Fremont Peak, East Temple, Mitchell Peak, Lizard Head, the Grand Teton, Mt. Whitney, and others. But until last week, I had never even laid eyes on my state’s tallest mountain. So excuse me for my exuberance, but now that I’m back in the lower regions, I’m remembering what I saw higher up…

And, just so you know, this is a very long blog post. As Mark Twain said, I would have written less, but I didn’t have time. I am behind at work from being in the wilds for 6 days, and yet I wanted to capture this experience, and to share it with others, while it’s so fresh in my mind. So, thank you in advance if you read what is a long-form article.

The very isolated Gannett Peak stands 13,809’ tall. It is the high point in all of Wyoming, and that fact is what draws many to the area to climb the mountain. For the record, Gannett’s status as being the high point in Wyoming is actually not the main reason I wanted to climb it. I was most interested in seeing what is very much, despite its height, a “hidden” mountain. I also wanted to see and travel over some of the last remaining glaciers in the Lower 48, including Gannett Glacier, on the north side of the peak, which is apparently the largest glacier in the Rocky Mountains south of the Canadian border. I’m always looking for interesting experiences, and climbing Gannett fit the bill, and then some.

I am in mountain climbing shape, and have years of backpacking experience, but I don’t have technical mountaineering expertise. So to climb Gannett, I signed on with Jackson Hole Mountain Guides for a guided expedition.

There were two others signed up for the same expedition – Rick, from Texas, and Robert, from Mississippi. Rick and Robert are “High Pointers.” If they could summit Gannett Peak, it would be #47 out of 48 for them. (BTW, since my return, I think I am talking with a bit of a Southern accent, the result of being around Rick’s and Robert’s charming southern voices for 6 days.)

Nate Opp would be our guide. Nate was one of the guides who led me up the Grand Teton in 2009, and I like his style, so I was psyched he would be the one facilitating the meaningful adventure for us.

From what I can tell, there are three ways to approach Gannett Peak, from the West, via Elkhart Park, or from the East, via Glacier Trail, near Dubois, WY, or via Ink Wells and the Wind River Indian Reservation (with permits, etc.)

The expedition would be six days, which at first to me, seemed like a long time required to climb a peak. (I don’t recommend it, but I’ve climbed Wind River Peak, and other lesser peaks, in a single day. Most often, though, I will take 3-4 days to hike a long ways and climb a single mountain peak in the Wind Rivers.)

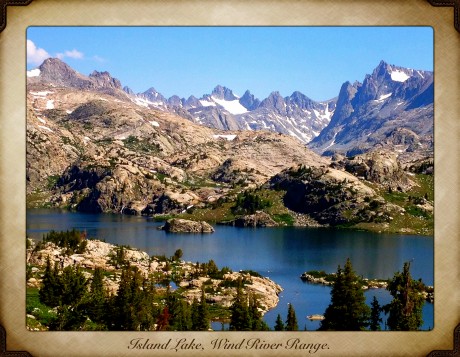

But when I looked at the maps, six days made perfect sense. Anything less than that, from the West side, seemed almost unreasonable, given variables like the weather, and snow depths and conditions, the altitude, etc. I could have signed on with another reputable company and approached from the East side, which was closer to my home of Lander, and the expedition would have required only 5 days’ time. But when I saw the route from the West approach, and realized it went through Titcomb Basin, I was even more excited. I had been into Island Lake and into Indian Basin (and up Fremont Peak) before and it is one of the most stunning regions I have ever seen.

“Summer breezes caressed me, my legs stepped forward as though possessed of their own appetites, and the mountains kept promising. I stopped before the trees were gone, not ready that day to disappear entirely into the vastness. Perhaps these spaces are the best corollary I have found to truth, to clarity, to independence.” – Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

Day 1: I love that quote from one of my favorite writers and books. We started at Elkhart Park trailhead, near Pinedale, WY. From there, we hiked 13 miles, passing many beautiful lakes, including Barbara, Hobbs, Seneca, Upper Seneca, Island and others. As soon as I started hiking, my legs stepped forward as though possessed of their own appetites, and the mountains kept promising…

We pitched our tents in Titcomb Basin, just past the Indian Basin Junction. We had a huge waterfall feature right near our tents, that included several cascades that drained into a lake that was below, in view from our tents. We had stellar views, including one filled with jagged granite peaks and glaciers that beckoned. If all went well, we’d soon find ourselves deep in those mountains and glaciers…

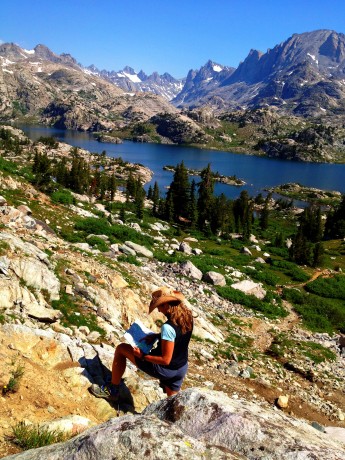

We hiked efficiently and arrived, and had our tents pitched by 3pm. I lounged around like a marmot on a big slab of granite under the warmth of the sun, while drinking in the waterfall soundtrack and the breathtaking views.

The lounging lasted only an hour or so before the weather changed drastically, and we raced for our tents. While in my tent, thunder echoed raucously against the granite towers that surrounded us, followed by lightning that lit up my tent. I am terrified by lightning, and this reminded me of a night at Clear Lake with my family that was the most scary night of our lives.

That night, lightning lit up our tent repeatedly and thunder roared as rain poured down for several hours. I never prayed so hard, and it felt miraculous that we had survived the night. I had hoped to never find myself so high up in a tent under those circumstances again, which I know is an unrealistic hope. If I am going to play in the high country, there will almost certainly be some thunder and lightning. (And it didn’t help that I recently read the fantastic book, A Bolt from the Blue, about the terrifying (and heroic) rescue in 2003 at 13,000′ on the Grand Teton. The page-turner-of-a-book tells the true story about a colossal lightning bolt that struck and pounded through the body of every climber in a group of six.

I know, I know – these things are not helpful when laying alone in a tent at 10,500′ that is getting lit up by lightning just seconds after raucous thunder echoes against the nearby granite mountains… I work with leaders and coach people all the time about the opportunity we have to “choose our mindset.” The late Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and a Nazi concentration camp survivor who wrote the influential Man’s Search for Meaning, argued that the last of the human freedoms that cannot be taken from us is our choosing how we will respond to our circumstances. I remembered this, and the work I do, and tried to change my “I’m going to be struck by lightning and die out here” mindset to “What a spectacular storm!” mindset. It didn’t work, but it wasn’t for a lack of effort.

So I lay there, uneasy and a little bummed that this adventure was off to this kind of start. I got out my journal and found notes from each of my three sons and my husband in the back. I read those a few times, and felt comforted. I know how blessed I am to have a family who supports these epic adventures of mine, and their thoughtfulness touched me. Luckily, the storm was short-lived. After about an hour and a half, the storm passed through, and we had blue sky and sunshine again.

After emerging from the storm, and our tents, Nate made us an epically delicious dinner of tacos, complete with guacamole, and peppers and salsa. We all ate like people who were super duper hungry. 🙂

I was getting to know Rick and Robert by now. After hiking several miles together, and now having shared our first meal together, we were acquaintances. I liked them immediately. They are kind, Southern gentlemen.

For the first time since starting Epic Life Inc., I chose to forego leading my flagship program, Epic Women, this summer. Every year at this time, I am leading my Epic Women expedition in the Wind Rivers. I coach women individually for several months, and then they all come together to meet for the first time, and we go into the wilderness to backpack and climb mountains.

This year, I wanted to do something personal instead. I was longing to do something new, and that would challenge me and expand my abilities. I also wanted to see some new sights, get inspired, to enjoy some solitude, and to not be in charge.

Like me, Rick and Robert were excited to be in the wilderness, and on an expedition to climb Gannett. Robert and Rick have been best friends for 40+ years. (It’s funny; I’m working right now on a project I’m calling Project Friendship. I’m reading a lot, and writing a lot, about friendship. I’m doing a lot of personal research on friendship, which is a source of great inspiration for me right now. And here on my Gannett Expedition, are two people who have been best friends for 4 decades. I always say, there are no coincidences…)

Robert and Rick are both avid drummers and musicians, and that’s how they originally met. For the last 10-12 years, they’ve been traveling the country bagging the high point in each of the states in the Lower 48. If they could stand on Gannett, it would mark their 47th of 48 high points.

After day 1, I felt reassured that the Universe arranged for Rick and Robert to be my trail comrades for such an epic adventure. And, we had a guide that I trusted. So far, so good…

“Being in the wild gathers me. It astonishes me. It quiets the negative voices inside of me and allows the more constructive ones to talk. It humbles me. It reminds me of how small I am, which has the reverse effect of making me feel gigantic inside.” –Cheryl Strayed

Day 2: We woke up at 7am, and had coffee while Nate cooked us a great breakfast of Huevos Rancheros. Mid-morning, we broke camp, and backpacked to the uppermost reaches of Titcomb Basin.

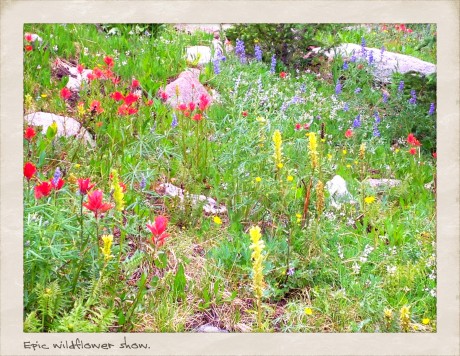

We hiked through wildflowers, snow, and alongside several lakes that were smooth as glass and that reflected the snow-capped, looming granite peaks in their waters. I was captivated the entire way. I’ve got many favorite trails and areas in my beloved Wind Rivers, and Titcomb Basin is at, or near, the very top of that list. It is incredible.

It’s impossible to not feel tiny in this country. And, as writer Cheryl Strayed so eloquently wrote, this has the reverse effect of making me feel gigantic inside. Huge, granite mountains towered above us as we hiked, and only a wide angle lens has any chance of capturing the alpine tundra, lakes and mountains in a single shot.

After about 6 miles, we pitched our tents as close to the base of Bonney Pass as possible. Ours was truly one of the most scenic campsites I have ever enjoyed. We were right under the towering Mt. Helen, and other tall peaks.

As I was pitching my tent, I spied movement out of the side of my eye. It was a herd of about 20 goats –- bighorn sheep ewes? I wandered quietly toward them and was able to watch them for some minutes. (see photo or video) We were all excited to see the wildlife, as we had only seen some songbirds, squirrels, marmots and pika, and weren’t expecting to see much in the way of wildlife on this trip.

Here’s a short video clip of the goats:

Our camp was surrounded by massive snow fields that adorned the towering peaks that jutted up from the alpine tundra all around us. We had a huge winter in Wyoming this year, and there was still abundant, melting snow all around us. And, close in our sight, was what would be one of the cruxes of our Gannett Peak summit ascent– Bonney (Dinwoody) Pass.

The pass is about 1,200 feet tall, and it’s steep (like in 45 degrees? steep), and mostly covered in snow. I have fitness for hiking up steep hills, but this would be different. We’d have crampons and helmets on. We’d be roped up. We’d have our ice axe at the ready for self arrest, and it would be, well, a serious undertaking, with high consequence should something go wrong.

The other thing about approaching and summiting Gannett from the West side is you have to not only go up Bonney pass, but down it, and across Dinwoody Glacier before you go up to Gannett’s summit. And, well, what goes up and down and up, goes down and up and down on the way back. It would be a truckload of hard-earned effort, and all of it technical and with high consequence.

I’ve hiked literally thousands of miles in these Wind River mountains during the last 20 years, but never had I spied with my own eyes the state’s tallest peak.

Gannett is remote, and very much hidden. So while I was a bit afraid of the task of ascending the steep pass, I could hardly contain my excitement for the sight that awaited me once we crested it.

Not only would I see Gannett Peak, but the map I studied indicated the view I’d get from the top of the pass would be full of glaciers. Last year, I climbed Fremont Peak with a friend, and was blown away when we got to the top of Fremont, and was rewarded by sights of the huge Fremont Glacier, and other glaciers in the distance. That sight had whetted my appetite. I wanted to see more glaciers in my backyard.

We enjoyed another great dinner that night, and we all talked nervously, but excitedly, about the next day’s plan.

I didn’t sleep a wink on night 2 because I just couldn’t wait to see Gannett Peak for the first time. I was just too excited for slumber.

“We cannot lower the mountain, therefore we must elevate ourselves.” – Todd Skinner

Day 3: Whenever I’m traveling, or camping in the wilderness, upon first waking, I always am a little disoriented and have to quickly search my brain for where I’m at. As my eyes first opened on Day 3, and I remembered where I was and what I was doing in Titcomb Basin, the above wise words are what came to mind. The late Todd Skinner was a friend, and a climbing legend, and an inspiration to so many. Today would be the first day of this expedition to really test my mettle.

I have leveled up my whole life. By leveling up, I mean I have signed up for or tried things I didn’t have the skills to do. Even though I may look like a fool, stumble, or fail, I believe in doing hard stuff. Abraham Maslow called it self actualizing, when we become actually what we are potentially. We can’t ever realize our potential without leveling up and daring to fail and doing hard stuff we don’t know exactly how to do. In short, I get a lot of fulfillment out of learning, and whenever I level up, I am guaranteed to learn new skills, not to mention more about myself.

Although we wouldn’t climb the mountain until Day 4, we’d start our “climb” today, on Bonney Pass. I was uncomfortable just thinking about what would be required. But as Todd said, we cannot lower the mountain, we have to rise up to meet it.

We were all up early, and Nate had coffee on for us before feeding us a breakfast that included bacon. Yes – you read correctly, bacon! Those who know me know that bacon is one of my favorite foods, so this made me extremely happy. The day was already a winner.

Nate was one of the guides who helped lead me to the Grand Teton’s summit in 2009. I like his style, and he’s very experienced, so although our adventure was full of uncertainties, one certainty was that we were in very capable hands.

During the previous day, and again over breakfast on Day 3, Nate shared and reviewed his vision for our expedition, which was to “slim our loads way down,” making them as light as possible while still carrying tent and sleeping bag, cook stove and food and clothing layers. We’d take our slimmed-down backpacks up and over Bonney Pass, down and across Dinwoody Glacier, before ascending a small outcropped ridge that’s situated about 2,000’ below Gannett Peak. There, we’d put in a camp for the short night before our summit attempt.

Nate explained this would make for a more reasonable summit day on Day 4, not to mention a richer overall experience. (Many who approach from the West side, via Elkhart Park, go up and over Bonney pass, across Dinwoody Glacier, then up to Gannett’s summit, and then all the way back. It can make for a 14-hour day for the most fit, and a 20-hour day for “average” adventurers, especially for those coming from sea level.) Even if we had the fitness for it, it didn’t sound very appealing, and Nate’s vision and reasoning were compelling.

When on a mountain climbing expedition, I want to climb a mountain, but I also want to maximize the experience. I’m willing to wake up at an hour in the wee hours of the morning to get a good start before the sun comes up, but if possible, I’d like for most of the experience to be during the light of day so I can see all of the awe-inspiring sights. I don’t want to experience half of the journey in the dark, and I want to be able to linger at least a little in such an awesome, and hard-to-get-to, setting. Add to that, ascending and descending the treacherous and steep Bonney Pass at the end of a Gannett Peak summit day is hard enough without having to do it twice in a single day. (That’s why when I climbed the Grand Teton in 2009, I opted for the 4-day experience with Jackson Hole Mountain Guides instead of the two-day option. I definitely had the fitness for the accelerated trip, but I wanted an optional summit day in case weather wasn’t favorable, and also, very importantly, I wanted to spend a night in celebration at the incredibly scenic high camp rather than rushing down a steep mountain to re-enter my civilized life more quickly than necessary.)

After breakfast and reviewing our plan, we cached the food and supplies we chose to leave behind, put our crampons and helmets on, and headed toward Bonney Pass.

At first it was easy going. We walked on a gradual uphill to the base of Bonney Pass, and I got used to walking on snow while wearing crampons. Once at the base of the pass, Nate roped us up and gave us some instructions.

Mountaineers rope up to mitigate the risk of of falling on steep, hard snow or ending up in a crevasse. Should a person fall on a steep snow slope, someone, or all, in the roped group will help to use their ice axes to stop the person from falling and/or pulling everyone down the slope with them. Or, if a person were to fall into a crevasse while traversing a glacier, being roped up and spread out will hopefully prevent that person from falling to his/her death or from suffering serious injury.

Nate explained we should keep the rope between each of us taut, not slack. Rick and Robert had much more experience with this kind of travel than I did. (They recently summited Mt. Rainier and Mt. Hood.) For me, this roped travel took some practice, but we were soon moving in a pretty good rhythm up Bonney Pass.

This day’s effort would be a quiet one. There’s not a lot of chit-chatting when you’re mountaineering over terrain that is treacherous, and where the risks are high. Intense focus is required. Your mind doesn’t wander. It can’t, and it doesn’t want to. Thankfully.

When we got about two-thirds of the way up the pass, Nate suggested we move to the rocks on the left to finish our ascent of Bonney Pass. Even though the rock was loose and the slope steep, with its own set of dangers, Nate explained the risk was less significant than a fall on the steep snow slope from upper Bonney Pass. So we de-cramponed, and while remaining roped together, scrambled our way up through boulders and over loose rock until we reached the top of Bonney Pass. At the top, we unroped, and Nate instructed us that once we crested the pass, we should take a load off for a few minutes to drink some water and eat a snack.

As we crested the pass, the hidden giant that is Gannett Peak revealed itself. It was tall like I expected, but it appeared more massive than I expected. I listened to hear the reaction of Rick and Robert and didn’t hear anything. (One of my very favorite parts about hiking with others in the Wind Rivers, is witnessing their reactions to the beauty that unfolds before them at different points of an expedition.) There was not a peep out of Robert and Rick. I smiled to myself because I assumed they were thinking what I was thinking. Excuse my language, but it went something like this: “Holy Shit.”

I was so excited at seeing Gannett for the first time, and in awe over all of the glaciers that lay before us. There was nothing but snow, glaciers, and towering granite peaks. The sight took my breath away, and mentally, was hard to process. (When I saw the Grand Canyon for the first time, my experience was similar in that I couldn’t find words to describe what I was experiencing, and it took a minute, or more, to fully process that what I was seeing was really real.)

Gannett Peak gets it name from Henry Gannett, who was an American geographer who is described as the “Father of the Quadrangle,” which is the basis for topographical maps in the United States. With 290 miles of isolation from a higher peak, Gannett is the most isolated peak in Wyoming, and the ninth-most isolated peak in the contiguous United States. With 7,076′ of clean prominence, the mountain is the most prominent peak in Wyoming.

It was certainly prominent as I looked at it, in awe.

We didn’t linger because we had a tall order ahead still, and an even taller order the next day. We finished our break, and put on our crampons again. Nate told me I’d go first on the descent. I don’t have much experience with crampons, let alone leading a group of people down a very steep and snow-covered mountain pass. I used crampons briefly, while ascending and descending a gully on my Mt. Whitney mountaineering expedition a few years ago, and briefly on my 2009 Grand Teton expedition, but nothing to this extent.

Did I mention how steep it was? When I asked how to proceed, Nate suggested I just go straight down the pass, with no switchbacking. To start, just try digging your heels in, he said. I used an ice axe in one hand and a trekking pole in the other to help balance myself, and away we went, slowly but surely, down Bonney’s very steep back side.

Up ahead, I could see several individuals coming toward us, spread out, appearing as tiny as ants, traversing Dinwoody Glacier.

The snowy slope we descended was full of “snow cups.” The sculpted cupped pattern of the snow resembled ocean ripples, only these were white snow ripples. Often, the snowy slopes we traversed, or ascended and descended, resembled corduroy with extra tall “ribs” that stretched the entire vertical length of the slope. It was beautiful.

By the way, four different times during a two-day period, I saw people I know. The Wind Rivers are vast, and remote, and no matter how many people I might know, I’m always surprised when I see someone I know in the remote reaches of the Wind Rivers. As we made our way down and across the lower portion of Dinwoody Glacier, we passed a guide who was roped up to a client. “Hi Shelli,” the client said. I didn’t recognize him at first because he had a helmet and glasses on, so I said, “Who’s that?” It was Kirk VanSlyke, a former Lander man who was a few classes ahead of me in high school. He now lives with his family in Dillon, MT.

As we continued, silence returned. The day’s work was quiet work. All I could hear was what would become a very familiar soundscape over the next several hours – our measured breathing, and the repeated sounds of our ice axes and crampons digging into the snow.

I noticed the longer I spent attached, literally, to Robert, Rick and Nate, the more connected I felt to them. Each of our safety depended on one another, and even though there weren’t a lot of words spoken when traveling over and through such high consequence terrain, a bond was developing over the course of our expedition. I could feel it, and found comfort in the fact that these guys had my back, and me, theirs.

I also found the single-minded, single-tasking a welcome reprieve from my busy mind. My mind is always thinking and tends to be future-oriented. Traveling on snow and up and down steep terrain, roped to one another, forced me to focus on only the next step, and then the next step, and then next step, for hours at a stretch. It was hard, but also unusual for me – and fantastic. The simplicity of it all was refreshing.

By 2:30pm, we reached the spot at almost 12,000’, situated directly under Gannett Peak, where we would pitch our tents for the short night. This was one of the most scenic campsites I’ve ever had. My tent was pitched under Gannett Peak, which I could clearly see, and on one side was Dinwoody Glacier, and on the other was Gannett Glacier. The rest of the scene was filled in by other glaciers, snow fields and tall, towering granite peaks.

Once we were out of our crampons and on level ground and safe and sound for the time being, I reflected on the day’s adventure. I felt exhilarated. It was a day of leveling up, of seeing new and astonishing sights, and I was filled with anticipation, and nerves, about the summit attempt that was only hours away.

Here’s a short video clip of tentsite at 12,000′, situated under Gannett’s summit and surrounded by glaciers and other tall mountains:

We ate an early dinner that hit the spot – cheesy potato soup with sausage and bacon bits. (Nate’s a great cook!) We reflected on the day’s effort, and agreed on a wakeup time of 3:30am for our summit day. The afternoon and evening were stellar. Blue sky, a fantastic warm and bright orange sunset, and a bright moon bid us good night as we headed into our tents early.

(I am probably being generous, but I think I slept about 20 minutes total. I never sleep well the night before a summit attempt, and well, this summit would be an extra big one for me.)

“You will either step forward into growth or you will step back into safety.” –Abraham Maslow

Day 4: At 3:30am, I woke up from not sleeping, and stumbled out of my tent with my headlamp on to find Nate boiling water for coffee and a quick oatmeal breakfast for us.

I have always wanted to climb things so I can see what the view is from “up there.” Today, specifically, I hoped to stand at the very top of Wyoming.

Our plan was challenging, yet simple: We’d summit Gannett, then return to our tents, break camp as quickly as possible, and continue down and across Dinwoody Glacier, and up and over Bonney Pass.

If it was just a matter of fitness, it wouldn’t be that big of a day. It would be hard, but not exceptional. But we had all kinds of variables to consider, not to mention risks. We’d be walking across and up snow, across and up glaciers, including the very steep Gooseneck Glacier, scrambling up steep sections of boulders and loose rock, and along Gannett’s exposed ridge which marks the final stretch to the mountain’s summit. And that would be just for the summiting portion. Then we’d reverse all of that, plus add some glacier travel, and a steep and high consequence ascent and descent of Bonney Pass at the very end of our day.

I won’t lie, part of why I signed up for a Gannett Peak climb was to push my limits. I wanted to step forward into growth a lot on this trip, and I knew today would deliver that, and then some.

At 5am, with headlamps, crampons and light packs on, we started up the snow to start our ascent of Gannett. After about 10 minutes of snow travel, we removed our crampons, restocked our water bottles from a spring, and then, roped up, and followed Nate up a steep section of boulders and loose rock.

My trail name is “Sunrise.” I got this name because the first light of day is my favorite time of day, and I often insist on starting in the dark so I can be in the wilderness or on the mountain when the sun comes up. So I was a happy camper when we were soon rewarded with a glorious sunrise! (Watching the sunrise made me recall the words of one of my favorite poems, Why I Wake Early, by Mary Oliver, which I know by heart: Hello, sun in my face | Hello, you who made the morning and spread it over the fields and into the faces of the tulips and the nodding morning glories, and into the windows of, even, the miserable and the crotchety – best preacher that ever was, dear star, that just happens to be where you are in the universe to keep us from ever-darkness, to ease us with warm touching, to hold us in the great hands of light – good morning, good morning, good morning. Watch, now, how I start the day in happiness, in kindness.

Next, we crossed a section of snow toward what’s known as the Gooseneck Glacier bergschrund, a crevasse that opens as the summer gets going and the snow melts. Lucky for us, while the bergschrund was starting to open, it had a “snowbridge”near/over it making it passable. The crux of the route begins here. The Gooseneck Glacier / couloir is steep and narrow, and makes your stomach turn when you look down and imagine the what ifs. I took a deep breath, and took some of the most deliberate steps of my life.

After getting up and through that section, we returned to class 3 rock scrambling, all the way up to the snow-covered face of Gannett, where we put our crampons back on to walk the ridge line to the summit. The final stretch was one of my favorite parts, and certainly one of the most exhilarating. The ridge is narrow, and on the left you can enjoy summit views of lakes and mountains everywhere below. As we made our way to the summit, we’d get glimpses through the rocky ridge on our left to all that was below and beyond. To our right was a steep, completely exposed, snow-covered face.

Compared to the rest of the effort, the final stretch to the summit is pretty level, even if it’s extremely exposed. I always feel at my fullest potential right before summiting – when the summit is in reach and right before I stand on it. I felt as though I was on top of the world, even if it was actually just on top my beloved state of Wyoming.

We enjoyed a half hour or so taking in the panoramic views and reflecting out loud about what we had just experienced. I sent a couple of texts with a summit photo to my husband and sons, my parents, etc., and then we reminded ourselves that that summit is only the ⅓ way point. (The saying usually is “The summit is only the halfway point.” And, in fact, most injuries occur on the descent of a mountain.)

In our case, we had to descend the mountain, break down our camp, and go down, and then up steep Bonney Pass and then descend the steep and treacherous Bonney Pass and eventually get back to our camp, hopefully in one piece, and hopefully before any significant changes in weather. It was a tall order. So we celebrated on top of Gannett, but not for too long, before descending, very carefully, 2,000’ to our tents.

We were methodical and efficient in our descent. After breaking down our camp in short order, we started our return journey.

Just as we imagined, ascending Bonney Pass was a grunt. We took a very short break at the top, and then braced ourselves for what Nate suggested might be the biggest crux of our day – getting safely down a treacherous Bonney Pass on tired legs and lungs. We remained roped up, but removed our crampons at the top of the pass, and followed Nate’s lead down a bunch of rock to mitigate the risk of a steep and dangerous fall on the top of Bonney Pass. About halfway down Bonney, we put our crampons back on and I took the lead and down we went, slowly, but steadily, so as to get this day’s adventure behind us as safely and as soon as possible.

We managed to get back to our main camp at the upper most reaches of Titcomb Basin by 5:30pm. We were all pretty wiped out, but it was great to be on firm and level ground, and finally, to fully celebrate what we had accomplished – standing on the top of Gannett Peak!

As per usual, Nate spoiled us with another hearty dinner. This time it was stuffing, mashed potatoes and gravy. We all ate as if we were very hungry mountaineers. It was a great feast, and we all recalled and replayed the events of the day. We were all filled with joy, but also a sense of relief. We had had success, and suffered no injuries or tragedies.

I shared with the group that my FitBit logged 20,547 steps for the day. And they weren’t just any steps. Every single one of those 20,547 steps were “high consequence” steps. Not many words were spoken during the 12-hour adventure, except for the short time on the summit, and when instruction was offered to us from Nate. Otherwise, Rick, Robert and I were completely focused on every single step. Until then, I had never engaged in such a sustained, high consequence experience. Being on the brink of safety, where the stakes were so high almost constantly, had the effect of making me feel so alive. (By the way, I can’t say enough how impressed I am with Nate, and other guides who must focus on their own individual steps and safety while carefully considering everyone else’s condition and every move.)

I have been fascinated by the concept of flow. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a Hungarian psychologist, named the psychological concept of flow and describes it as “a highly focused state.”

Recently, I’ve read books about flow, including The Rise of Superman, and a more recent follow up book, Stealing Fire.

There are 17 triggers that can lead to flow state, and by all indications, this mountaineering experience we were having included several of them. One thing that is required to reach the flow state of mind is intensely focused attention. Check. Another flow trigger is having a clear goal. Check. We were very clear about our goal. There was no wondering about what our plan was each day on the expedition. Another trigger is the challenge-to-skill ratio. Check. For flow to occur, you need to be doing something that is harder than you’re capable of doing – that requires skills you may not yet have. This will prevent boredom while keeping you engaged and at attention for long periods of time. Another requirement for flow is high consequence. Check. Since we left our camp in the morning, every single step we took, and there were thousands according to my FitBit, were of high consequence. Rich environment is another flow requirement. Check. We were surrounded by a unique environment, rich in glaciers and tall and beautiful mountain peaks. Deep embodiment is another flow trigger. Once again, check. Deep embodiment means total physical awareness. This is when we harness the power of our whole body and pay attention to the task at hand. This also means paying attention to multiple sensory streams at once. No question, my senses were heightened every step on this day. I never felt so alive… even if I was mentally exhausted when we finally returned to our Upper Titcomb Basin camp.

But I digress…

While it was a physical endeavor for me, Gannett taxed me mentally more than it did physically.

So no surprise, once I could let my mind loose, I slept. Hard.

We all slept in, and it was a blissful experience. We had coffee and ate breakfast, and had one of many great mealtime conversations. As is often the case, the deeper we got into the expedition, the more we each let our guards down, and the more meaningful our conversations became.

Around lunch-time, we broke camp and started our 6-mile hike back to our original camp. We all were still high from our accomplishment and the shared experience. Since today’s was a hike rather than a mountain climb, there were more words. At times we hiked together, but at others we spread out. I don’t know about Rick, Robert and Nate, but I spent my hike on Day 5 replaying the previous days’ events, and recalling the scenery I saw, and also taking notice of all of my spectacular surroundings.

I often go to the wilderness to be alone. I think Solitude is the medium for self realization, and I often yearn for time alone. I have a lot of natural enthusiasm and energy, but I also suffer depressive periods every now and again. I know from experience that getting away and going into the wilds is medicine for my soul. I think about this as I walk alone ahead of the group on Day 5. These days in the wilderness have done me good.

I was reminded of a quote I highlighted in one of my favorite books, a Field Guide to Getting Lost, by Rebecca Solnit:

“As you step up to the ridgeline… The world doubles in size.”

I knew I would return from this trip as more than I was before.

We had a glorious last night in the wilderness. We had a pasta dinner, and chocolate for dessert, and then enjoyed a sunset that painted the granite walls and peaks around us a deep pinkish-orange. The moon was bright, and almost full. Rick and Robert and I enjoyed the sunset together, and shared more stories and memories with one another, in between our reflections of what we had all experienced and accomplished together.

Here’s a short video clip of our last night in camp:

I went to my tent feeling extra blessed. I had not only climbed Wyoming’s tallest mountain, but I also made two new friends, and reconnected with a guide I deeply respect. I especially felt grateful for my family, who lovingly supports these adventures I want to experience, and felt, once again, restored and rejuvenated by my beloved Wind River mountains.

Day 6: Our last day’s hike out was about 13 miles. I couldn’t wait to see Jerry and the boys. They hiked in to meet me when I had about two miles left. They are the best support team a person could ever dream of having and I had a few happy tears when I spied them coming toward me.

(Side note: I was hiking particularly fast on this last day not only because I was eager to be reunited with my family, but also because I was chasing/trying to hunt down a friend of mine that I’ve never met in person. Her name is Kara, and she lives in New York. We have common interests and some mutual friends. Before our respective expeditions, we compared notes and discovered we’d both be somewhere in the Titcomb Basin region on Aug. 4 and early on the 5th. I looked for her on the trail on Aug. 4, but to no avail, and I tried to catch her on my hike out on Aug. 5. I had asked many incoming hikers if they had seen a group of four women, including one with braids and a headband, which is how Kara described herself when we agreed by email to look for each other “out there.” At one point, a hiker informed me that Kara and her group were only 1.5 miles ahead of me, but that was with only about 3 miles remaining to the trailhead, and unfortunately, I couldn’t close the gap!

As if seeing my family wasn’t enough to make for a perfect ending to my Gannett Peak expedition, Jerry had a cooler of cold beers, an assortment of fresh fruit, and bags of salty chips ready for Nate, Robert, Rick and I at the “finish line.”

As I wrap this up, I’m also grateful for friendship, and the two new friends I made in Robert and Rick. I am looking forward to keeping in touch with them. I also am grateful for Nate, and for his skills and his leadership. Without him, I couldn’t have made this dream come true.